International Lessons for Developing Elementary Teachers

The latest report from the National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE) Center for International Education Benchmarking analyzes how four high-performing systems around the world develop elementary teachers with deep content and pedagogical understanding. An accompanying policy brief makes a case for employing these practices in order to strengthen primary education, setting students up for success in high school and beyond.

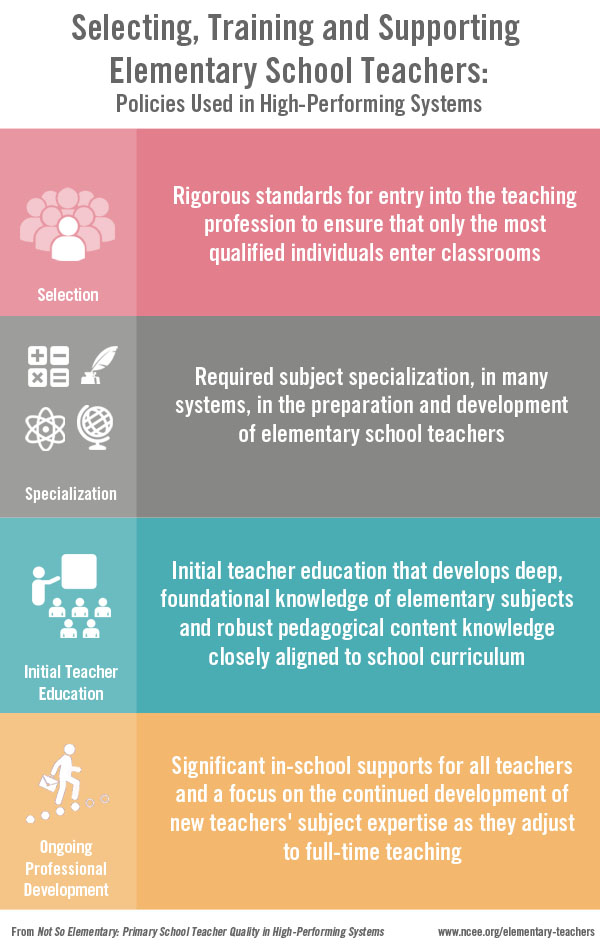

In the report, Not So Elementary: Primary School Teacher Quality in Top-Performing Systems, authors Ben Jensen, Katie Roberts-Hull, Jacqueline Magee, and Leah Ginnivan focus on practices in Finland, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Japan. Although the U.S. system is not included in the analysis, the report offers comparisons of the four high-performing systems and draws lessons for ours around four key components of elementary teacher development: selection, content specialization, preservice teacher preparation, and in-service professional learning.

Marc Tucker, president and CEO of NCEE, connected the report’s key points to the U.S. system in a press release. “We now face an enormous challenge: raising the segment of high school graduates from which we recruit our elementary school teachers, demanding much deeper grounding of prospective teachers in the subjects they will teach, and, at the same time, raising the game of the teachers already in our schools,” he said.

AACTE President/CEO Sharon P. Robinson joined a panel of experts responding to the report’s release in a webcast last week. Downplaying the less useful comparisons of the disparate systems, Robinson reflected on the findings to identify practices whose core intent might translate well to the United States.

To match candidates’ course work and content preparation with the needs of local schools, for example, Finnish teacher candidates receive the curriculum at the beginning of their preparation program and then work on mastering it throughout their program. In U.S. teacher preparation, Robinson noted, clinical development models provide candidates close relationships with both content and context.

“We have a very strong network of programs that are developing symbiotic relationships with school districts and other partners in practice to develop new teachers’ skills, based on the real curriculum to be taught in those schools,” she said, citing the thriving professional development school model and the work of AACTE’s Clinical Practice Commission.

The side-by-side comparisons of the four systems provide food for thought on several fronts. They differ considerably from one another, for example, in their selection processes and in the degree to which they prepare elementary teachers as generalists or specialists.

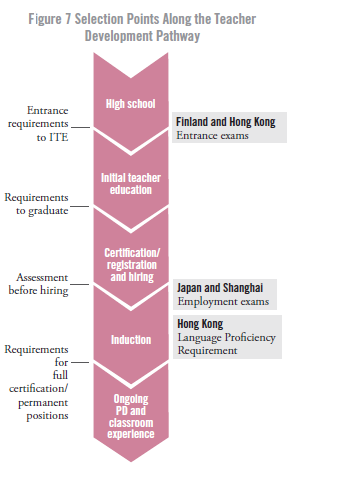

For candidate selection, Finland and Hong Kong use a rigorous admissions system, whereas Japan and Shanghai are more open for entry and rely on a stronger screening process at the point of licensure/employment (see graphic below).

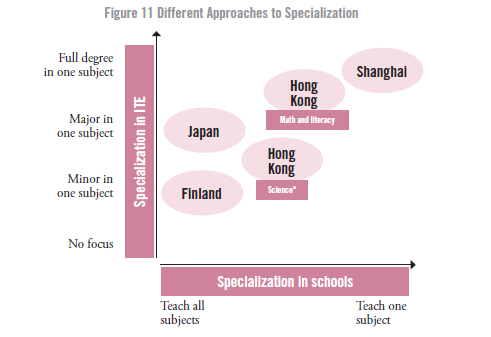

Regarding specialization (see graphic below), Japan and Finland–like the U.S.–are generalist systems, meaning that their elementary school teachers teach all subjects required by the curriculum. In Hong Kong, primary teachers are not full generalists, but they do teach some subjects outside of their specialty. Shanghai elementary teachers specialize fully, earning a degree in and teaching only one subject. The report argues that greater teacher specialization helps pupils develop deeper content understanding while potentially decreasing teachers’ workload and allowing them to focus on what interests them most.

Among the report’s suggestions for U.S. policy:

- Focus initial teacher preparation on foundational content at the elementary level, including pedagogical content knowledge, and align the preparation with the local school curriculum.

- Rather than relying on a minimum standard for proficiency that offers no differentiation among candidates other than pass/fail, consider continuous measures of expertise and/or more transparent assessment data.

- Use specialization to foster deeper subject expertise in elementary school teachers. Schools with fully specialized teachers might follow the Shanghai model of looping, allowing teachers to develop multiyear relationships with the same cohort of students. Schools with generalists who have deep knowledge in one subject might hire and assign teachers strategically to ensure each subject has at least one expert teacher.

- Ensure all teachers continue in-service development of their subject expertise and pedagogical content knowledge, especially in the first few years. Consider induction programs with subject-specific collaboration, such as the Japanese model of lesson study.

Robinson praised the report’s focus on pedagogical content knowledge and noted that U.S. programs are working to address teacher quality at multiple points of intervention. “Our teacher preparation programs have admissions standards appropriate to the mission of the institutions,” Robinson said, “but performance-based selection measures at licensure or hiring are critical. We also need to consider the distribution of expertise as a factor in staffing schools.”

For more information and links to the report, webcast, and related resources, see http://www.ncee.org/elementary-teachers/.

Tags: elementary education, global issues, research, workforce development